LEAVING NO ONE BEHIND: SOCIAL PROTECTION AND DISABILITY IN THE PACIFIC

Leaving no one behind: Social protection and disability in the Pacific

Written by P4SP and the Pacific Disability Forum (PDF)

Access the easy read version of the blog.

Women with disabilities attending the capacity building training organised by PDF for Organisations of Persons with Disabilities (OPD) in Samoa, July 2023. Photo by PDF.

Over the past decade, the Pacific region has emerged as a leader in providing formal social protection for persons with disabilities, despite facing unique geographical and economic challenges. Significant strides have been made in delivering disability benefits and continued progress will contribute to greater income security and wellbeing for persons with disabilities.

The Pacific context

Prior to formal social protection systems in Pacific Island countries (PICs), and continuing alongside them today, traditional social protection mechanisms have played a vital role for persons with disabilities. These safety nets encompass family and community networks. The family unit traditionally acts as the first line of carers and support, with immediate and extended family members serving as primary caregivers. This aligns with Pacific cultural values of collective responsibility and reciprocity (Mohanty, 2011).

As in many places around the world, persons with disabilities have been among the most marginalised groups in the Pacific region, facing stigma, discrimination and exclusion. For women and girls with disabilities, these challenges are compounded by intersecting forms of discrimination based on disability and gender. Women with disabilities face prejudice stemming from harmful assumptions and norms about their status and capabilities in both domains (UNDP, 2009).

Social protection has been identified by PDF as one of the ‘Preconditions for Inclusion’ in the Pacific region to help respond to the extra costs of disability. A key challenge to delivering social protection programs is the Pacific’s diverse geography. From the remote highlands of Papua New Guinea to the scattered atolls of the North Pacific, the vast distances and logistical constraints drive up the costs of service provision and limit accessibility for persons with disabilities. As a result, they have historically been overrepresented among the region’s unemployed and poor. At the same time, the number of persons with disabilities in the Pacific is rising due to aging populations and the increasing prevalence of non-communicable diseases.

This comes at a time when fiscal pressures across the Pacific region have been acute. Many countries in the region had long sustained structural fiscal deficits, but the COVID-19 pandemic and the associated economic downturn have exacerbated the situation. The large fiscal stimulus packages (averaging 15% of GDP) linked to the pandemic have broadly increased debt levels and placed further pressure on existing government expenditure (P4SP, 2024b).

The Pacific’s commitment to supporting people with disability

Pacific governments and NGOs have taken proactive steps to strengthen social protection for persons with disabilities. Pacific Disability Forum was established in 2002, recognising the need for a regional body to represent people with disabilities. From 2008, a number of Pacific countries also began to ratify the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), which includes explicit recognition (Article 28) of the right of persons with disabilities to an adequate standard of living and social protection, and introduced new or revised national disability laws. In 2009, the first Forum Disability Ministers’ Meeting was held in Cook Islands, which endorsed the first regional strategy for persons with disabilities. This momentum continued with the Pacific Framework for the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (PFRPD), which identifies strengthening social protection as one of its ten fundamental goals, acknowledging social protection’s important role in supporting the independence and dignity of persons with disabilities (PIFS, 2016).

While the ratification of the CRPD and development of inclusive policies mark important progress, implementation remains a significant challenge across the Pacific. The gap between policy commitments and practical inclusion persists, highlighting the critical need for continued advocacy and awareness-raising. Recognising this, PDF works to equip Organisations of Persons with Disabilities (OPDs) with comprehensive knowledge about social protection systems. When OPDs understand these systems, they are empowered to participate meaningfully in policy discussions and advocate effectively for the rights of persons with disabilities. PDF’s work in building this advocacy capacity and raising awareness throughout the Pacific region has become increasingly vital in bridging the implementation gap and moving from policy promises to practical inclusion.

Disability benefits in the Pacific

The approach in the Pacific aims to align with global best practice, strengthening social protection for persons with disabilities through a twin-tracked approach: mainstreaming social protection access to everyone living with a disability; and introducing disability-specific social protection schemes. The former ensures that all social protection programs and systems are designed and implemented in ways that are inclusive of persons with disabilities. The latter, which includes disability benefits and carers’ benefits, are critical for providing additional income support to help persons with disabilities manage their higher costs of living. There are strong examples of both these approaches being implemented across the Pacific region.

Disability specific programs—namely disability benefits—are one of the newest features of the social protection landscape in the Pacific region. Since 2015, six countries have introduced disability benefits—Fiji, Kiribati, Palau, Samoa, Tonga and Tuvalu (P4SP, 2024b). These benefits are non-contributory and provide regular, predictable payments to persons with disabilities (benefit amounts can vary depending on support needs). Disability benefits are a critical element of the globally endorsed social protection floor, which ensures basic income security for people across all stages of the lifecycle.

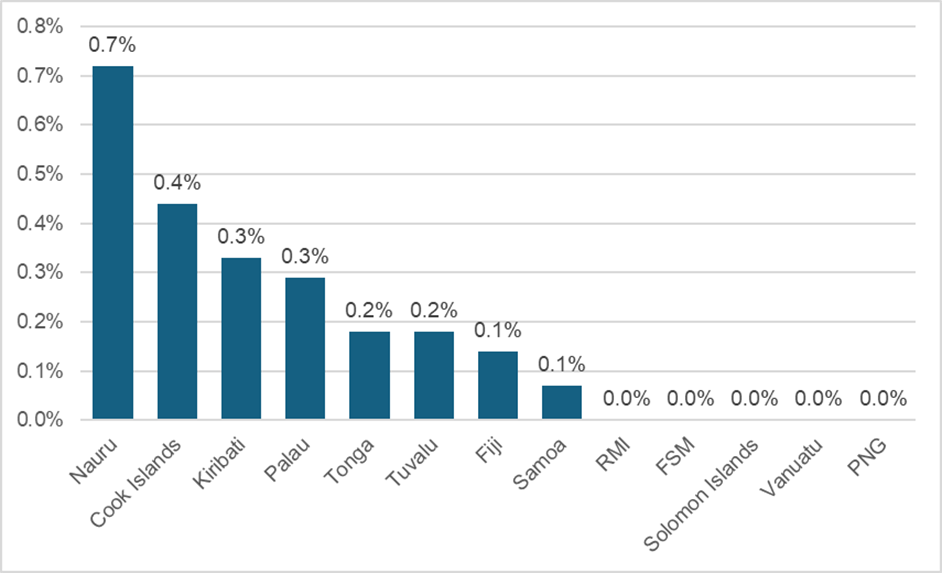

While general coverage rates for social protection programs in the Pacific are relatively low, coverage rates for persons with disabilities are higher than many other regions globally and well above peer countries. Some countries, such as Nauru, Cook Islands and Kiribati, are proportionally among the highest spending countries on disability benefits globally (Figure 1). All I-Kiribati citizens with disabilities are eligible for all social protection programs, including a disability benefit. This means that the high proportion of the elderly with a disability are entitled to both a generous old age pension and a disability benefit, providing these citizens with a high degree of income security.

Figure 1. Expenditure on disability benefit programs (as a share of GNI)

Source: P4SP, 2023.

Opportunities to maximise impact

The Pacific has made significant progress in disability programs, and there are opportunities to further enhance their impact through thoughtful program design.

Integrating gender-responsive elements into social protection schemes can better address the unique challenges faced by women with disabilities. These include lower literacy rates, limited mobility and transport options—especially in rural areas—reduced workforce participation, and higher poverty rates (SPC, 2023).

Ensuring disability benefits are sufficient to cover the extra cost of disability is another key area for improvement. While some Pacific countries, such as Kiribati, provide relatively generous benefits (about 18% of GNI per capita), others fall short in compensating for extra disability related expenses like care support, support services, assistive devices, rehabilitation, healthcare, and transportation. Given the region’s remoteness, these costs are often higher than in other parts of the world.

Making disability benefits compatible with work is another potential area for reform. The purpose of disability benefits is not to create dependency nor discourage employment, but rather to provide the necessary support to offset the extra costs that come with disability. This support should enable, not hinder, workforce participation. While Fiji’s Disability Allowance Scheme permits beneficiaries to engage in productive work, other Pacific countries still exclude employed individuals from receiving benefits (P4SP, 2024a). This highlights a critical need to reframe disability benefits as an enabler of participation rather than a substitute for employment.

Beyond financial aid, addressing the underlying barriers that persons with disabilities face is crucial. This includes access to healthcare, rehabilitation, employment assistance, accessible transport, housing, and independent living support—particularly for women, who face disproportionate challenges. While cash benefits help alleviate to some extent the financial pressure, this needs to be complimented with service delivery and support services. Success in implementing these support services depends heavily on strong partnerships between government, disability service providers and OPDs. When governments actively engage with OPDs, policies and programs are more likely to effectively meet the needs of persons with disabilities. Some Pacific nations are making strides in this area.

A final opportunity lies in shifting towards a rights-based approach for disability assessment. Currently, many disability benefits in the Pacific rely primarily on medical models of disability assessment, which create barriers to access, particularly for those in rural and remote areas. This places significant responsibilities on persons with disabilities to obtain medical documentation, made more challenging by the shortage of medical specialists like psychiatrists and occupational therapists across Pacific Island Countries. Even where medical expertise is available, assessments often fail to capture daily lived experiences and environmental barriers. The medical model's requirements are especially burdensome for those in remote islands, who must travel long distances at considerable expense to access assessments, inadvertently excluding many who might qualify for support. While medical professionals provide valuable expertise, their assessments alone may not fully reflect the social, environmental and cultural contexts that impact participation in society. A more holistic functional assessment, as Fiji has adopted through the Disability Allowance Scheme, may provide a blueprint for other Pacific countries.

Leaving no one behind

The Pacific is setting a global example for how social protection can be leveraged to provide much needed economic security and ensure the dignity of people living with disabilities. While there is scope for strengthening disability-specific social protection in the region, Pacific governments show that with political will and fiscal commitment, progress is possible. The last decade has presented a challenging set of fiscal circumstances for the Pacific with the COVID-19 pandemic, driving many countries towards record deficits and debt levels. Despite this, there has been growing and steady investment in social protection for persons with disabilities across the region—a true testament to the Pacific way of leaving no one behind.

This blog was first published on socialprotection.org and is republished here with permission.

Disclosure: Partnerships for Social Protection is an Australian Government program implemented by Development Pathways.

This publication has been funded by the Australian Government through the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. The views expressed in this publication are the author's alone and are not necessarily the views of the Australian Government.

Reference list:

Emberson-Bain, A. (2021). Inequality, Discrimination and Exclusion: Assessing CRPD Compliance in Pacific Island Legislation. United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific. https://repository.unescap.org/handle/20.500.12870/4043

Knox-Vydmanov, C., & Cote, A. (2023). The path towards inclusive social protection for people with disabilities in the Pacific. DevPolicy Blog. https://devpolicy.org/the-path-towards-inclusive-social-protection-in-the-pacific-20231017/

Mohanty, M. (2011). Informal social protection and social development in Pacific Island Countries: Role of NGOS and Civil Society. Asia-Pacific Development Journal, Vol.18, No.2, 25-56. https://www.unescap.org/sites/default/files/2-Mohanty.pdf

Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat. (2016). Pacific Framework for the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

Partnerships for Social Protection (2023). Database of social protection expenditure in Pacific Island Countries and Timor-Leste – August 2024 edition.

Partnerships for Social Protection (2024a). Disability and social protection in the Pacific and Timor-Leste topic brief. Partnerships for Social Protection and Australia Aid.

Partnerships for Social Protection (2024b). Investing in social protection in good times and bad: An assessment of social protection financing in the Pacific and Timor-Leste.

Partnerships for Social Protection and Australia Aid. Pacific Community (SPC). (2023). Thematic Brief: Inclusion of Pacific women with disabilities.

UNDP. (2009). Pacific sisters with disabilities: at the intersection of discrimination.