ADDRESSING INFLATION IMPACTS IN THE PACIFIC: THE ROLE OF SOCIAL ASSISTANCE

Addressing inflation impacts in the Pacific: The role of social assistance

By Charles Knox-Vydmanov

Rising global energy and food prices have added to inflation in the Pacific, leading to higher living costs over the previous two years. While exposure to inflationary shock has varied across the region, nearly all countries were affected to some degree, with the Cook Islands, Samoa and Tonga experiencing double digit inflation in 2021.

As social protection contributes directly to household incomes, this can be a useful tool to help combat the impact of inflation spikes—an effect recognised by many countries worldwide.

Over the previous decade, Pacific governments have increased spending on social assistance. A study by the Australian Government’s Partnerships for Social Protection program, Investing in social protection in good times and bad: An assessment of social protection financing in the Pacific and Timor-Leste, explored how these measures have helped combat inflation impacts.

Do social protection benefits meet people’s needs in the Pacific?

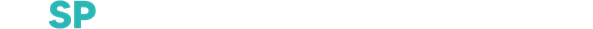

To understand how social protection meet people’s needs, known as adequacy, the study measured benefits relative to gross national income (GNI) per capita. This shows how Pacific island countries (PICs) compare globally. Focusing on the two most common schemes in the Pacific—old age and disability benefits—gives a mixed picture (Figure 1).

Benefits in Fiji, Nauru, Tonga and Tuvalu fall below the international average of around 15 per cent of GNI per capita for such benefits, while benefits in Cook Islands and Timor-Leste are above that average. It should be noted that many of the countries where the impacts of disability benefits are best evidenced—such as Brazil, Mauritius and South Africa—are those with benefits above this global average. Also, disability benefits tend to be lower than old age benefits, despite the fact that children and persons of working age with disabilities may face similar, if not higher, disability-related costs as older persons.

Figure 1: Benefit levels of disability and old age benefits in PICs, Timor-Leste and selected countries, % of GNI per capita

Source: UNICEF (forthcoming); ESCAP and ILO (2020)

In most cases, social assistance benefits only partly contribute to providing a basic level of income security, meaning that recipients need to rely on other sources of income and support from work and family. The low level of benefits in many countries means that their role in protecting individuals and families from inflation is inherently limited.

Have benefits kept pace with prices?

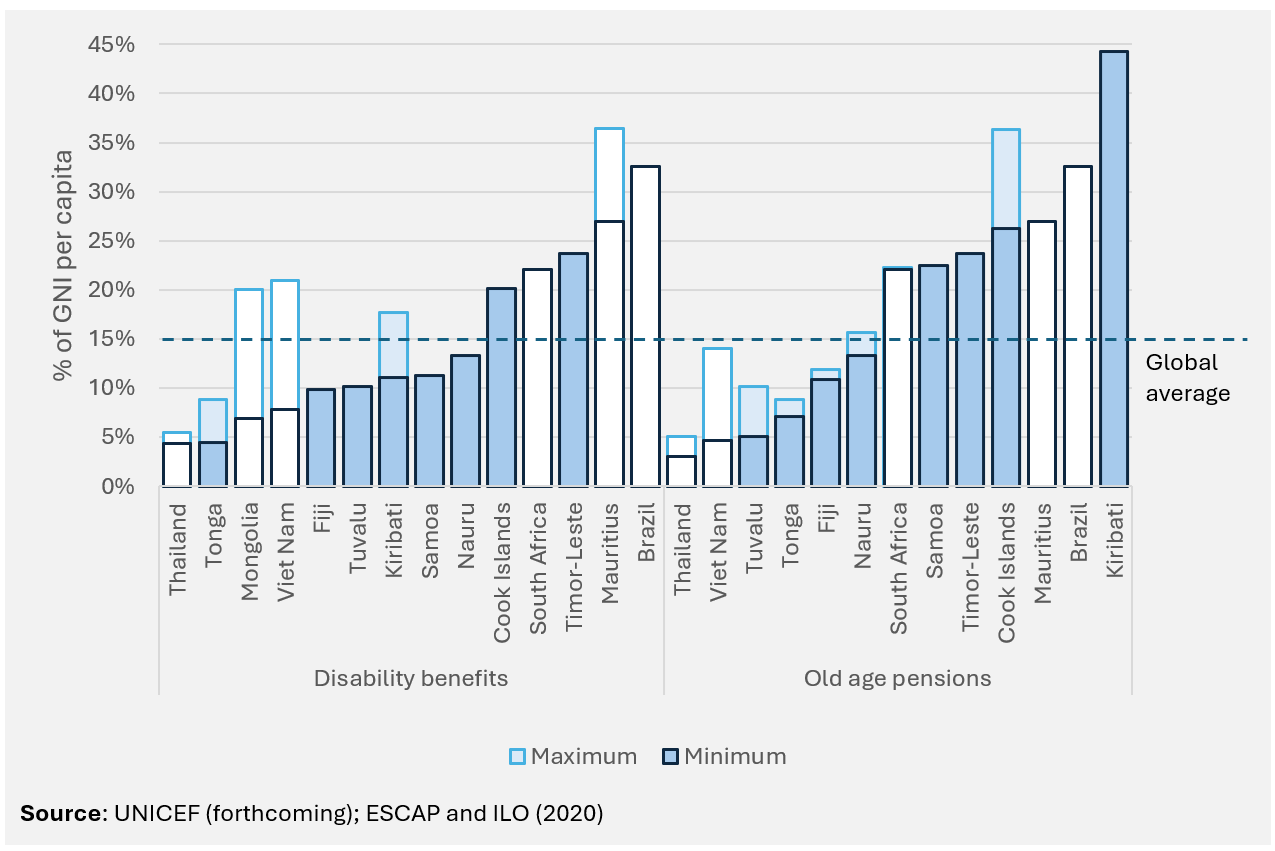

Social assistance schemes in PICs are not governed by rules that systematically adjust benefits in line with inflation. This is unlike some more developed countries that index some of their benefits. In the Pacific, benefit levels are instead adjusted on an ad hoc basis, sometimes with many years passing between increases in benefit levels.

Tuvalu’s old age and disability benefits shows the consequence of this approach. While the benefit level has been increased twice since the Senior Citizen Scheme’s introduction, the real value has been eroded each time by inflation in subsequent years (Figure 2). While the purchasing power in 2023 was 29 per cent higher than when the scheme was introduced, this was well below the value in 2019 when the benefit was last increased (65 per cent higher than at introduction). The pattern is even more extreme in other countries, with Timor-Leste’s old age and disability benefit having fallen by 40 per cent in real terms between 2008 and 2022 (before an increase in 2023).

Figure 2: Tuvalu – Senior Citizen Scheme and Disability Support Scheme

Note: The Disability Support Scheme was introduced in 2015, with a benefit level equal to the maximum benefit under the Senior Citizen Scheme (for persons aged 70 and over).

Despite these dynamics, some countries including Fiji and Samoa use their social assistance system to address price inflation. In late 2022, Fiji launched significant “inflation mitigation” measures. This involved making additional one-off payments to existing social assistance benefit recipients and setting up a new temporary scheme for children aged up to 18. While the child benefit scheme was means tested, the threshold was relatively high. It was estimated the scheme covered most school age children, and around two thirds of those below school age. Following these measures, regular social assistance benefit levels were increased under the 2023-24 budget. As a result, Fiji avoided a dip in the purchasing power of benefits in 2022, while providing additional short-term support for children and continuing a sustained increase in the real value of benefits in 2023.

Dual track strategy to soften inflation blows to households

The study highlights how a dual track strategy can fully leverage social assistance to protect households from inflationary pressures. Firstly, governments could continually review social assistance benefit levels—not only relative to inflation—but also based on the needs of and costs faced by target populations. Secondly, PICs could consider formally indexing social protection benefits to price inflation. This requires careful analysis of the fiscal context in each country; however, it is worth noting that in many cases the cost of inflation-indexed benefits will fall over time as a share of government expenditure and GNI. While many countries in the region have used social protection to mitigate inflation impacts, a more systematic approach to adjusting benefits in line with rising costs can contribute to greater income security for the people who need it most.

Related publications: